By Adam Hunerven

Soon after I arrived in Ürümchi in 2014 I met a young Uyghur man named Alim. He grew up in a small town near the city of Khotan in the deep south of the Uyghur homeland near the Chinese border with Pakistan. He was a tall, quiet young man who had come to the city looking for better opportunities. Critical of many of the rural people with whom he had grown up, he saw them as lacking capitalist ambition and an understanding of the broader Muslim world. But he was even more critical of the systemic, ongoing issues that had pushed Uyghurs into migrant labor and limited their access to Islamic knowledge. There were far too few economic opportunities and far too many religious and political restrictions in the rural areas of Northwest China, he explained. Since the beginning of the most recent “hard-strike campaigns” that lead up to the implementation of the “People’s War on Terror” (Ch: renmin fankong zhanzheng) in May 2014, many people in the countryside had reached a new level of despair and hopelessness.[1] Alim told me: “If suicide was not forbidden in Islam many people would choose this as a way out.” After praying in the mosque he often saw men crying in each others’ arms—the promise of future redemption matched by the brokenness they felt in their own lives. “Have you seen the Hunger Games?” he asked. “It feels just like that to us.” But it was hard for him to put into words what, exactly, this felt like. He was grasping for a cultural script with which to contextualize the devastating feeling of being so powerless. As a young Uyghur male, he was terrified that he would be caught up in the counter-terrorism sweeps. Every day, he tried to put the threat out of his mind and act as though it was not real.

As I got to know Alim better, he began to tell me more explicit stories about what was happening to his world. “Most Uyghur young men my age are psychologically damaged,” he explained. “When I was in elementary school surrounded by other Uyghurs I was very outgoing and active. Now I feel like I ‘have been broken’” (Uy: rohi sunghan). He told me stories of the way that friends of his had been taken by the police and beaten, only to be released after powerful or wealthy relatives had intervened in their cases. He said, “Five years ago [after the protests of 2009] people fled Ürümchi for the South (of Xinjiang) in order to feel safer, now they are fleeing the South in order to feel safer in the city. Quality of life is now about feeling safe.”

By 2014 the trauma people experienced in the rural Uyghur homeland was acute. It followed them into the city, hung over their heads and affected the comportment of their bodies. It made people tentative, looking over their shoulders, keeping their heads down. It made them tremble and cry. Many Uyghur migrants to the city had immediate relatives who remained in the countryside and with whom they stayed in touch with over social media. Rumors of what was happening in the countryside were therefore a constant part of everyday conversation. Once, meeting Alim in a park, he said that a relative stationed at a prison near Alim’s hometown had told him what was happening there. Over the past few months many young Uyghur women who had previously worn reformist Islamic coverings had been arrested and sentenced to 5 to 8 years in the prison as religious “extremists” who harbored “terrorist” ideologies. As he spoke, Alim’s lower lip trembled. He said the Uyghur and Han prison guards had repeatedly raped these young women, saying that if they did this “they didn’t miss their wives at home.” They told each other “you can just ‘use’ these girls.” Alim told this story in a very quiet voice, hunched over on the park-bench. His knee was touching mine. His shoe was touching mine. Among Uyghur men, having an intimate friend means sharing the same space and sharing each others’ pain. Nearby a Uyghur woman was shaking apple trees, while two other women filled bags with small stone-sized apples (Uy: tash alma). I looked away from Alim so that I wouldn’t cry.

Many Uyghurs repeated such claims. They described beatings, torture, disappearances and everyday indignities that they and their families suffered at the hands of the state. At times these stories seemed to be partial truths, but many times the level of detail and the emotional feeling that accompanied these stories made them feel completely true. Part of the widespread psychological damage that Alim mentioned above, came precisely from hearing about such things in an atmosphere that makes all kinds of atrocities possible. Even if the individual claim might be false in some instances the particular type of violence it describes was probably occurring nonetheless, or it would soon. As a result the Uyghur present was increasingly traumatic and there was no end in sight.

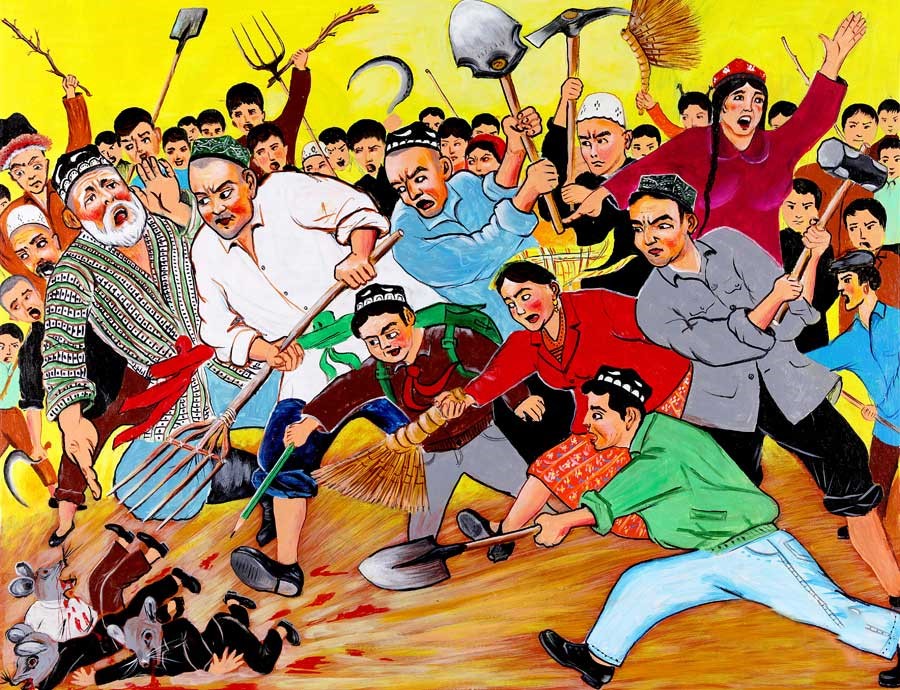

A painting titled “Rats Crossing the Street” produced as part of a “People’s War on Terror” art competition among rural Uyghur villages in 2014. The representation of “bad Muslims” as rats, a reflection of the way Xinjiang party secretary Zhang Chunxian described unsubmissive Uyghurs, is an example of the dehumanizing effect of the terrorism discourse.

Part 1

How did the Uyghurs become a Chinese minority?

In official accounts of its rule of Chinese Central Asia, the Chinese state positions itself as the inheritor of an empire that is over two thousand years old. Although the nineteenth century Chinese name for Chinese Central Asia (Xinjiang, or “New Frontier”) belies this history, the state nevertheless describes the Uyghur homeland of contemporary Southern Xinjiang as an inalienable part of the nation. In official histories, the intermittent presence of military outposts administered by the progenitors of the contemporary Han ethnic majority, first during the Han Dynasty and then centuries later in the Tang and centuries later again in the Qing, lends a feeling of continuity of rule across the millennia. In these histories the fact that the region spent nearly 1000 years outside of the control of Chinese empires is unacknowledged. These state histories do not acknowledge the fact that state-sponsored migration of people identified as Han from Henan, Shandong, Zhejiang and elsewhere did not reach more than 5 percent of the population of the region until the 1950s. It is rarely mentioned that Xinjiang was not named an official province-level territory until 1884, following what in the Uyghur oral tradition is referred to as a “massacre” of native Muslims by a general from Hunan named Zuo Zongtang and his armies.[2] These Muslims, the ancestors of contemporary Uyghurs, had attempted to regain their sovereignty in the 1820s and 1860s, much like they would again in the 1930s and 1940s.

Instead of acknowledging the centrality of native sovereignty in the Uyghur homeland throughout its history, in its narration of Xinjiang’s history the contemporary Chinese state emphasizes “the liberation” of the Uyghurs and other native groups by the People’s Liberation Army in the 1940s.[3] Non-Han groups are often represented as living in “backward,” “feudal” conditions in “uncivilized” (Ch: manhuang) lands prior to the arrival of their socialist “liberators” from the East. Since the 1949 revolution, so the self-valorizing narrative goes, Uyghur society has entered into a tight harmony with their Han “older brothers.” Their solidarity in shared socialist struggle is said to have resulted in ever-increasing levels of happiness and “progress.” Uyghurs and the 10 million Han settlers who have arrived since 1949 are said to share a great deal of equality and “ethnic solidarity” (Ch: minzu tuanjie). Yet only minorities are thought to possess “ethnic characteristics” (Ch: minzu tese). Both the sophisticated Han liberators and the “ethnics” (Ch: minzu) are described as happy citizens of the thriving nation. Of course, despite this rhetoric of economic liberation and harmonious multiculturalism, all is clearly not well between Uyghurs and the state. In fact, since almost the very beginning of the People’s Republic in 1949, the Uyghurs have experienced diminishing levels of power and autonomy relative to Han settlers, and, as Alim’s stories demonstrate, increasingly they experience high levels of fear.

Chinese Central Asia or Xinjiang is located in contemporary far Northwest China. It borders eight nations ranging from Mongolia to India. The largest group of people native to this large province are the Uyghurs, a Turkic Muslim minority that shares a mutually-intelligible Turkic language with the Uzbeks, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz. Like the Uzbeks, Uyghurs have practiced small-scale irrigated farming for centuries in the desert oases of Central Asia. At present there are approximately 11 million people identified as Uyghurs according to official Chinese state statistics, though local officials estimate that there may be as many as 13 million. At the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the population of Han-identified inhabitants of the region was less than five percent, with Uyghurs comprising roughly 80 percent of the total population. Today Uyghurs comprise less than 50 percent of the total population and Han more than 40 percent. This shift in demographics began in the 1950s when the Chinese state moved several million former soldiers into the region to work as farmers on military colonies in the northern part of the province. These settlers, members of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (Ch: bingtuan), were sent to the borderlands in an effort to secure the frontier against the expansion of the Soviet Union. The primary goal of this project was not to assimilate native populations, but rather to transform Kazakh pastureland into irrigated farming colonies, redistribute the population of former soldiers, and secure the territorial integrity of the nation.

Although Uyghur lifeways were deeply affected by the socialist reforms of this era, Uyghurs continued to live in Uyghur majority areas in Southern Xinjiang until the 1990s, when private and public investment brought new infrastructure to their homeland. Since these projects began, millions of Han settlers have moved into Uyghur lands to work in the oil and natural gas fields and transform Uyghur oasis cities into centers of transnational commerce. This more recent development has had a strong effect on local autonomy, because it has significantly increased the cost of living for Uyghurs while at the same time largely excluding them from new development projects. The commonly held perception of Chinese state occupation of Uyghur lands has prompted widespread protests among the Uyghur population. In response to this discontent, the state’s response has been to increase efforts to forcibly assimilate Uyghurs into mainstream Han society by transforming the education system from Uyghur-medium to Chinese-medium, and by implementing ever-tighter restrictions on Uyghur cultural and religious practices. At the same time, new communication infrastructure, such as smart phones and region wide 3G networks, have given Uyghurs access to a broader Islamic world that was previously unavailable to them. This has produced a widespread Islamic piety movement among Uyghurs. Although in most cases this movement is simply a Uyghur adaptation of mainstream Hanafi Sunni Islam,[4] it has been interpreted as a wave of “religious extremism” by local authorities. This turn toward new forms of religious practice has been linked by Party officials, often quite tangentially, to violent incidents involving Uyghur and Han civilians. Following a series of such incidents from 2009 to 2014 both in Xinjiang and in other parts of China, on May 26, 2014 the party secretary of the province, Zhang Chunxian, along with Xi Jinping, announced a special state of emergency that they labeled the “People’s War on Terror.”

Since the implementation of this ongoing state of emergency, the situation for Uyghurs has become increasingly dire. Rising Chinese Islamophobia has been joined by rising American Islamophobia and tactical support from private security firms connected to the Trump administration.[5] The widely reported activity of several hundred Uyghurs in the Islamic State has lent credence to Chinese claims of wide-spread “extremism” among the whole Uyghur population of 11 million people. As a result, nearly all Uyghurs are now seen as guilty of “extremist” tendencies and subject to the threat of detention and reeducation. Tens of thousands of Uyghurs, particularly young men under the age of 55, have been detained indefinitely.[6] In many cases, children have been taken from Uyghur families and are being raised in Chinese language boarding schools as wards of the state.[7]

The state of emergency in contemporary Xinjiang is more than a simple “ethnic conflict” or “counter-terrorism” project. It is instead a process of social elimination that is being applied to a people native to Northwest China that joins the racialized dispossession inherent in capitalist development to the racialized policing that is inherent in the rhetoric of terrorism. Throughout its history, capitalism in Europe and North America has incorporated a form of “original” capital accumulation that was naturalized through the production of ethnic or racial difference. These differences were used to justify the dispossession and domination of minorities. While the modern Chinese state’s socialist developmental scheme was markedly different from European and North American projects, this difference no longer appears to hold sway in a time of terror. Despite their position within the socialist history of the nation, “terror” now frames Uyghurs as “subhuman”, much like the framings of native populations as “savages” during the European and North American wars of conquest and accumulation.

Part 2

The Effects of the Chinese Politics of Ethnic Recognition

In Europe, the lexicon and practice of imperialism was shaped by the way French colonists looked to the Russian Empire as a model of conquest, and in turn by the way the Russian imperialists looked to the US conquest of Native American lands as a model for their own colonial efforts in the steppes and deserts of Siberia and Central Asia.[8] This genealogy of Russian colonial thinking is important because it decenters the dominance of Western Europe as the progenitor of empire and colonial expansion. In fact, Chinese imperial projects in the Qing dynasty and Republican-era China were also mobilized around “a virulent form of racial nationalism” vis-à-vis other Asian populations precisely out of the comparative process of empire building.[9] Late-Republican reformers looked to their nearest competitors Japan and Russia, and the British Empire to the South, as they too built their nation on the scaffolding of dynastic rule.

The process of political and material expansion of the People’s Republic of China into Chinese Central Asia in the early 1950s was characterized by relationships of domination and projects of social engineering and elimination. As in the Soviet Union, the PRC followed a logic of sociocultural reengineering under the guise of eliminating “counterrevolutionary” threats. Of course, threats of “local nationalism” were in many cases simply a euphemism for ethno-racial difference and native sovereignty.[10] In Xinjiang the fact of native Uyghur existence was thus one of the primary obstacles to the nation-building project. This challenge produced multiple outcomes. On the one hand, the state strove to diminish the religious and cultural institutions of Uyghur society while, on the other, it sought to create a new socialist society on native lands. Although the lack of infrastructure, poverty and linguistic difference slowed the completion of this process of reengineering, the overall goal of the PRC settler state was from the beginning one of access to land and resources and the ongoing elimination of all obstacles that stood in its way.

In an effort to achieve its reengineering objectives, the Chinese ethnic minority paradigm that was instituted in 1954 laid out particular forms of permitted difference in minority societies.[11] This process was enabled by social scientists who began to use ethnology, particularly linguistic anthropology—borrowed from British and Russian colonialists and shaped by older Han-specific modes of identification—in order to identify “nationalities” (Ch: minzu) on the peripheries of the young People’s Republic.[12] The identification of China’s multinational demographics broadened certain categories and disintegrated others into a legible index of discrete ethnic minorities. Thirteen groups, including the Uyghurs, were thus identified in Xinjiang. By the late 1950s, many Uyghur cultural and religious institutions—ranging from schools to mosques—had been transformed into institutions of the developmental regime. This form of minority recognition served the purpose of forcing a native group to participate in a narrative of “harmonious” socialist multiculturalism. It also defined improper forms of difference, opening them to state control. This form of human engineering depended on the placing of people within essentialized ethnic or indigenous ascriptions while at the same time deeply restricting the authority and autonomy of native religious and cultural institutions. After 1957, leaders of Uyghur social institutions were appointed by the state,[13] and the content of permitted Uyghur cultural institutions was itself selected and codified by the state. In the hierarchy of the nation, minorities in China, particularly those who were phenotypically marked as racially different (Tibetans, Mongolians, Uyghurs and Kazakhs), were slotted into subservient “little brother” social roles. Han “liberators” on the other hand described themselves as “big brothers.”

In the Uyghur case, multiculturalism, as a relation of Han domination over minorities, resulted in a widespread invention of new cultural categories. Under the direction of Zhou Enlai in the early 1950s “teachers, scholars and experts” were sent to teach Uyghurs how to be ethnic.[14] By the mid-1950s the identification process began to codify cultural practices and oral traditions in relation to an imposed ideology: song and dance troops abounded, ethnic costumes were identified and essentialized, and new genres of socialist literature and performance were invented.[15] The decentralized forms of oral tradition and indigenous Muslim sacred space that were central to the knowledge systems of the people native to the Uyghur homeland were thus shaped into a manageable form for the Chinese state.[16] As in the British and Russian colonies, differences were permitted and encouraged as long as they did not conflict with the dominant ideals of the state.

This cultural transformation also directly impacted the organization of Uyghur life. During the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), many families in the Uyghur homeland were moved from single family homesteads into village communes in which every building was the same height and daily meals were shared. As in other parts of China, work was collectivized and the surplus not ceded to the state was shared. Although populations of Han workers were moved into state farming colonies in Northern Xinjiang, Uyghurs continued to live in Uyghur dominated areas in Southern Xinjiang. In the early period of the PRC, socialist multiculturalism was strongly felt by Uyghurs in terms of an imposed ideology and in forms of production and consumption. Yet, a lack of infrastructure and resources prevented the full assimilation of Uyghur society into the Chinese nation. In fact, during this period Han-identified officials who were stationed in the Uyghur homeland often learned Uyghur and became active members of Uyghur communities. Young Uyghurs still grew up speaking Uyghur. Many rural Uyghurs did not meet native Chinese speakers until the 1990s, when a widespread transformation of the Xinjiang economy brought millions of people who identified as Han to the Uyghur homeland.

After the Second Liberation: Socialist Legacies and Capitalist Development

Fulfilling the old model of multiculturalism was further complicated by the emergence of market liberalization in Xinjiang beginning in the early 1980s. As the state moved in fits and starts from socialist development to capitalist accumulation and the accompanying suppression of “terrorism,” the displacement of native lifeways became more acute. Many Uyghurs refer to the 1980s as a “Golden Era” when the possibilities of life seemed to open up. The relative economic, political and religious freedom that accompanied the Reform and Opening Period seemed to promise a brighter future. Many Han settlers, who had come to the northern part of the region during the Maoist campaigns to secure the borderlands, were permitted to return to their hometowns in Eastern China. But with the collapse of the Soviet Union in December of 1991 and the independence of the Central Asian republics, the Chinese state was suddenly faced with rising tensions regarding Uyghur desires for independence. At the same time the fracturing of Russia, China’s long-term imperial rival, offered new zones for building Chinese influence. Even more importantly, it created opportunities to access energy resources. A chief concern among state authorities in the region was that the new freedoms that Uyghurs had enjoyed in the 1980s threatened to flower into a full-throated independence movement. As Uyghur trade relationships increased in the emerging markets of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, and cultural and religious exchange with Uzbekistan was rekindled, the Chinese authorities became increasingly concerned that Uyghurs would begin to demand the autonomy they had been promised in the 1950s. The state was deeply concerned that the newly independent republics of Post-Soviet Central Asia would serve as allies in the Uyghur struggle for greater autonomy. As a result of these concerns, the underlying goal of the Chinese state’s attempts to control Central Asian markets and buy access to its natural resources became that of ensuring “that these states do not support the Uyghur cause in Xinjiang or tolerate exile movements on their own soil.”[17]

At the same time that the Chinese state was extending its control in post-Soviet Central Asia, it also announced a new policy position that would turn the Uyghur homeland into a center of trade, capitalist infrastructure and agricultural development capable of further serving the needs of the nation. One of the primary emphases of the new proposal was the need to establish Xinjiang as one of China’s primary cotton producing regions. Given the exponential growth in commodity clothing production in Eastern China in the 1980s, the state was determined to find a cheap source of domestic cotton to meet the accelerating demand for Chinese-produced t-shirts and jeans around the world.

As a result of this initiative, infrastructure investment in Chinese Central Asia expanded from only 7.3 billion yuan in 1991 to 16.5 billion in 1994. Over the same period the gross domestic product of the region nearly doubled, reaching a new high of 15.5 billion.[18] Much of this new investment was spent on infrastructure projects that connected the Uyghur homeland to the Chinese cities to its east. By 1995 the Taklamakan Highway had been completed across the desert, connecting the oasis town of Khotan (Ch: Hetian) to Ürümchi, cutting travel time in half. By 1999 the railroad had been expanded from Korla to Aqsu and Kashgar, opening the Uyghur heartland to direct Han migration and Chinese commerce. Over the same period the capacity of the railways leading from Ürümchi to Eastern China were doubled, allowing for a dramatic increase in natural and agricultural resource exports from the province to the factories in Eastern China.

As infrastructure was built, new settlement policies were also put in place. Like the settler policies from the socialist period, these new projects were intended to both alleviate overcrowding in Eastern China and centralize control over the frontier. But unlike those earlier population transfers, this new settler movement was driven by capitalist expansion as well. For the first time, Han settlers were promised upward mobility through profiting in the cash economy and capital investment. Initially this enterprise, formally labeled “Open Up the Northwest” (Ch: Xibei kaifa), was centered around industrial scale cotton production. The state put financial incentives in place to transform both steppe and desert areas for water-intensive cotton cultivation by both native Uyghur farmers and increasing numbers of Han settlers. As part of this process they introduced incentive programs for Han farmers to move to Xinjiang to grow and process cotton for use in Chinese factories. By 1997 the area of cotton production in Xinjiang had doubled relative to the amount of land used in 1990. Most of this expansion occurred in what had been Uyghur territory between Aqsu and Kashgar. In less than a decade, Chinese Central Asia had become China’s largest source of domestic cotton, producing 25 percent of all cotton consumed in the nation.

Yet despite this apparent success, important concerns began to emerge as well. Chief among these was the way the new shift in production and settlement was affecting the native population. Many Han settlers profited from their work in the Xinjiang cotton industry as short-term seasonal workers who received high wages, as settlers who were given subsidized housing and land, and as managers of larger scale farms. But many of the Uyghurs who were affected by the shift in production did not benefit to the same degree. They were often forced to convert their existing multi-crop farms to cotton in order to meet regionally imposed quotas. They were also forced to sell their cotton only to Han-run state-owned enterprises at low fixed prices. These corporations in turn sold the cotton at full market price to factories in Eastern China. In this manner many Uyghur farmers were pulled into downward spirals of poverty, while many (though not all) Han settlers continued to benefit from the shifting economic trends. Labor exploitation coupled with dispossession gave rise to increasing feelings of oppression and occupation. These feelings continued to increase as the need for cheap sources of energy increased in the rapidly developing cities of Eastern China.

By the early 2000s, the Uyghur homeland had come to resemble a classic peripheral colony. In the context of the nation as a whole, the primary function of the province was to supply the metropoles of Beijing, Shanghai and the Pearl River Delta to the East with raw resources and industrial supplies. Cotton production continued as it had in the 1990s, but by the early 2000s industrial tomato production had also been introduced as primary export product. By 2012 the region produced approximately 30 percent of world tomato exports.[19] A similar movement was true for the natural gas and oil that began to flow to Eastern China from Xinjiang after the completion of pipeline infrastructure in the early 2000s.[20] Within a few short years, oil and gas sales came to represent nearly half of the region’s revenues. By the early 2000s the Uyghur homeland had become the country’s fourth largest oil producing area with a capacity of 20 million tons per year. Given that the area had proven reserves of petroleum of over 2.5 billion tons and 700 billion cubic meters of natural gas, there can be no doubt about how the region was thought of as one of China’s primary future sources of energy.[21] At the same time, as in most peripheral colonies, the vast majority of manufactured products consumed in Xinjiang came from the factories in Eastern China. The clothes manufactured using Xinjiang’s cotton was being thus purchased back from clothing companies in Eastern China at inflated prices.

Given the push to reduce the nation’s dependence on foreign cotton, oil and gas, as well as to accelerate the settler-colonization of the Uyghur homeland, during this period the central government continued to provide nearly two-thirds of the region’s budget. In the early 2000s the Hu Jintao administration took the older regional project “Open up the Northwest” to a new level, rebranding it as “Open up the West.” Now all of peripheral China, including Inner Mongolia and Tibet, became the target of settlement and development projects, though Chinese Central Asia continued to receive a greater number of new settlers relative to other regions. Given the way the older “Open up the Northwest” project had resulted in rapid and sustained economic growth of over ten-percent-per-year since 1992, the state was eager to take the development projects further, opening new markets and new sites for industrial production.[22]

Between 1990 and 2000 the population of Han settlers grew at twice the rate of the native population. The development of fixed capital investments and industrial agriculture export production that accompanied the “Open up the West” campaign had the effect of rapidly increasing the rate of Han settlement in Uyghur and Tibetan areas.[23] By the late 2000s, the Han population had superseded the size of the Uyghur population, though it was still not a majority of the overall population and in many areas Uyghurs were still the large majority.

The lucrative chaos of rapid development and dispossession produced tremendous opportunities in real estate speculation, natural resource development and international trade for Han settlers, but has produced exponential increases in costs of living and widespread dispossessions of Uyghurs from land and housing.[24] The costs of basic staples such as rice, flour, oil and meat have more than doubled. While urban housing prices have doubled or tripled, projects to urbanize the Uyghur countryside have placed Uyghurs in new housing complexes that are dependent on regular payments for centralized heat and power. The system of small-scale mixed-crop farming with small herds of sheep and garden plots has also been undermined through this process. Underemployment has been exacerbated by the widespread consolidation of Uyghur land into industrial farms and, more recently, restrictions on labor migration.

This capitalist chaos has increased indebtedness among Uyghurs, who are systematically blocked from low interest lines of credit by nationalized banks, which place restrictions on loans to Uyghurs due to their assumed disposition toward the “three forces” of Islamic reformism, national self-determination, and violent resistance. According to many Uyghur migrants, Han landlords or bankers have increasingly found ways of evicting Uyghur business-owners or homeowners and replacing them with Han settler tenants. Many Uyghur migrants note that they encountered prejudice when seeking loans or authorizations of sales and purchases.[25] Meanwhile, banks and landlords are often quite eager to provide Han settlers with loans for purchases of real estate or discounts on business investments.

An insidious ethno-racism is often the driver behind such decisions. Uyghurs, unlike Han settlers, are often seen by Han lenders as not possessing the discipline necessary for capitalist development. As the Xinjiang state economic advisor Tang Lijiu put it, “Because of their lifestyle, asking (Uyghurs) to go into big industrial production, onto the production line: they’re probably not suited to that.”[26] For many Han businessmen, dealing with Uyghurs is seen as just too much “trouble.” It was for the same reason that Uyghurs are told they need not apply for high-skilled jobs in natural resource development, which are universally controlled by Han settlers. Because of the supposed threat that Uyghurs pose as potential “terrorists”, to the vast majority of Uyghurs, the state also refuses to issue legal documents in order to travel and trade domestically and internationally. As a result, native minorities frequently find themselves caught in the downward spiral of poverty even as the Han society that is growing around them has grown increasingly affluent.

Posters that depict the appearance of “good Muslims” and “bad Muslims” that were posted throughout the Uyghur districts of Ürümchi in September 2014. Those that appear to be “bad Muslims” were subject to immediate arrest. Image by Nicola Zolin

The rapid corporate development and Han settlement of the Uyghur homeland coupled with the arrival of “terrorism” rhetoric has had the effect of adapting older forms of socialist multiculturalism into a distinctly capitalist process of racialization. This process became particularly apparent after the beginning of the United States’ “Global War on Terror” in 2001, when nearly all forms of resistance by Uyghurs began to be described as terrorism by the Chinese state and in Han popular culture. The “dark” bodies of Uyghur men became synonymous with danger and “wild” (Ch: yexing) virility. This way of describing Uyghur bodies has become institutionalized by the police and government officials through frequent state media reports on Uyghur protests. Many officials and Chinese terrorism experts that I interviewed described Uyghur young men explicitly in these terms. In 2014, posters were placed throughout Uyghur districts of Ürümchi depicting and labeling the appearance of rural-origin religious Uyghur young men and women as evidence of terrorism (see the above image). Police actively profiled low-income rural-origin Uyghur youth at checkpoints. This institutionalization of power over the bodies of Uyghurs defines these phenomena as not simply features of ethnic discrimination but as an expansive process of racialization, comparable to similar processes that took place within the US, the British Empire, and places like South Africa.[27]

Yet many accounts of the violence that has occurred in this region describe it as an “ethnic conflict,” placing it in the same category as internecine violence elsewhere in the “developing world.” What such accounts ignore is the possibility of new sequences of racialization, comparable to the institution of Apartheid in South Africa or the violent segregation of Palestine, perhaps since Han themselves have often been the subject of European and American racism. The racism that is being produced in the Uyghur homeland through contemporary processes of racialization is, of course, unique to this particular moment and this particular place. It is nonetheless important to name such processes as racial, rather than ethnic or cultural, because it enables us to see how economic and political institutions sediment differences among groups. Naming this process as racialization centers the way capitalist exploitation is embodied. Individual workers’ inner characteristics are framed by legal, economic and educational institutions “through their skin color, dress, language, smell, accent, hairstyle, way of walking, facial expressions, and behavior.”[28] Uyghurs have been, and continue to be, subject to a particular form of racialization, driven by the Chinese state and the Han settlers under its purview. This racialization provides an a priori justification for expansive institutions of control and the populations they benefit, even while these institutions are themselves constantly producing and reinforcing the process of racialization itself, in the form of direct ethnic domination over the Uyghur population.

Part 3

The Terror Shift

The power of the ethno-racial imaginary of inclusiveness or multiculturalism has been both a blessing and a nightmare for minority peoples in China.[29] On the one hand, such a politics of inclusion reduces the impulse toward a mass physical genocide of the type seen in early North American colonization. On the other hand, it creates a false sense of “goodness” on the part of the colonizer and misrecognizes systemic racism. In contemporary China, colonized minorities such as the Mongols, Uyghurs and Tibetans “have often been criticized for loving their own groups too much. Their self-love has been denounced as minzu qingxu (nationality sentiment).”[30] This sentiment or spirit is said to manifest as “separatism,” “terrorism,” and religious “extremism.” It results in “hate crimes” (Ch: chouhen zuixing) by minorities toward members of the “good” majority who have “liberated” their territories by settling them and bringing them modern economics and Han morality. Crimes of being too native are of course crushed by the state. But even as the state crushes dissent, many Han, who consider themselves “good people” on the side of socialist inclusion, ask the question: “Why do they hate us so much after we have done so many good things for them?” The lack of an independent Chinese press and academia forecloses the possibility of having an open critical dialogue about why only minority-on-Han crime can be categorized as hateful or terroristic.[31] Instead “good” inclusive Han citizens of the nation feel compelled to teach ungrateful Uyghurs a good lesson in being tolerant of Han moral instruction. Minority claims to the sovereignty of their own land, faith, language, knowledge and being can thus be read as “bad”, as resistant to Han goodness.

The moral bankruptcy of the Chinese multicultural project came to a head when in 2009 Uyghur protests in Ürümchi over the mob killing of Uyghur factory workers by Han factory workers turned into widespread violence. In the months that followed, state authorities began a process of urban cleansing that directly targeted low-income Uyghur communities.[32] Many Uyghur areas of Ürümchi and other traditionally Uyghur cities were targeted for demolition and over the next few years the Uyghur migrant populations were moved into tightly controlled government housing on the outskirts of cities. Their land was turned into commodity housing for Han settlers and real estate speculators. At the same time, the state began to institute a radical shift from Uyghur-medium education to Chinese-medium education throughout the province. In 2010 the state introduced smart phones and 3G networks across the countryside as a way to link Han settlements and extraction infrastructure to the rest of the nation. One of the latent consequences of this new development was that Uyghurs were exposed to new ways of understanding the practice and instruction of Islam. Over the next four years many Uyghurs became involved in global piety movements that were introduced to them via their new Internet access. A small minority of those who turned to new forms of orthopraxy were drawn into contemporary conservative political or Salafi Islam, but the vast majority simply began to practice mainstream forms of Hanafi Sunni Islam. After four short years of relatively open use of social media to promote the thought of Uyghur Islamic teachers in Turkey and Uzbek teachers from Kyrgyzstan, the state instituted new restrictions on Islamic practice.

The People’s War on Terror

In May of 2014 after an increase in Uyghur violence toward Han civilians—first through a mass killing at a train station in Kunming, then a mass killing in a Han street market in Ürümchi and a suicide bombing at the Ürümchi train station—the state declared a “People’s War on Terror” centered on rooting out Uyghur Islamic reformist practices (or “extremism”), national independence (or “separatism”) and violent resistance (or “terrorism”). As in many other parts of the world, the concept of “terrorism” in China was strongly influenced by Bush Era North American political rhetoric. Prior to September 11, 2001, Uyghur violence was almost exclusively regarded as nationalist “separatism.” Since 2001, according to official state reports Han settlers in Xinjiang have become victims of “terrorism” on a regular basis. [33] By 2004, “splitist” incidents from the previous decade were relabeled as “terrorist” incidents.[34] Everything from the theft of sheep, to a land seizure protest, to a fight with knives can now be labeled “terrorism” if there are Uyghurs and Han involved in the conflict. It appears as though “terrorism” (or the “three forces” continuum—separatism, extremism, terrorism—which are now understood as manifestations of the same phenomenon) has come to signify Uyghurs who are verbally and physically unsubmissive and “unopen” (Ch: bu kaifang) to Han cultural values. Now Chinese “terrorism” has come to be “any perceived threat to state territorial sovereignty, regardless of its actual methods or effects vis-à-vis harm to others.”[35]

Passbook Systems, Home Invasions and Mass Detentions

This rhetoric of terror was taken to a new level with the 2014 “People’s War on Terror” against the Uyghur population of the country. One of the first things instituted under the emergency provisions of “the war” was a passbook system that restricted the movement of Uyghur migrants.[36] This system, known as the “People’s Convenient Card” system (Ch: bianminka; Uy: yeshil kart) required Uyghurs whose household registration (Ch: hukou) was not in an urban location to return to their hometowns and obtain a “good citizen” card in order to return. Like the passbook system that was instituted in Apartheid South Africa, the goal of this system was to force the unwanted racial other from locations that were desired by the settler population.

Based on my interviews, the most typical process for obtaining the card was as follows:

1. Applicant asked for a bianminka from local police. He or she was told to come back tomorrow when the “holder of the stamp” will be there. That person was often either not there the next day or was not receiving visitors. Eventually the applicant was formally denied or gave up on the formal process.

2. Applicant went to the home of the village leader of the local “production brigade” (Ch: dadui) at night. Applicant presented all of the documents he or she has proving that he or she was from: (a) a “5 star” family based on the marks they had been given by the local police on the gate of their house; (b) Father and mother had a good peasant background (no religious training etc.); (c) It was helpful to prove that poor economic circumstances necessitate that a member of the family must migrate in order to financially support the family back in the village; (d) absolutely no “extremist” religious ideas were present in the applicant or in family members of the applicant (including cousins, uncles etc.). Applicant also gave the team leader a “small” (Uy: kichik) gift of around 500 yuan, telling him that he or she knew it was not enough, but please “accept this humble gift” and so on.

3. If the team leader was convinced, he told the applicant which member of the local government to contact. The applicant was told to go to that officer’s home at night with a gift of 1000-4000 yuan (in some places the regular rate was 1000; in others 4000; in others, as much as 10000) in an envelope. The team leader told the applicant that under no circumstances should he or she tell the officer that he sent the applicant to the officer. The team leader also told the applicant to wait one week or more before visiting the officer so it would not be obvious that the night visits to the people’s homes were related.

4. After visiting the officer and delivering the bribe, the applicant was told that within a certain amount of time they would receive a phone call and they could come in to get their bianminka.

Needless to say it was very difficult for Uyghur migrants to obtain this card. Only around one in ten were able to do so.[37] This resulted in around 300,000 Uyghur migrants to the city of Ürümchi and hundreds of thousands of migrants to regional centers such as Korla, Aksu and Kashgar being forced to leave. Without the card it was impossible for them to rent housing, find a job or even stay in a hotel.

By May of 2016 the system was taken to a new level. At this time, even if Uyghurs had the card, those without urban household registration were not allowed to leave their home counties without permission. There were checkpoints between every county, and crossing the county line required a letter and with a stamp from local authorities. As a result, even those who previously had legal permission to live in Ürümchi and other urban locations were now forced to return to the countryside. Often when they arrive back in the countryside they are subject to detention.

Following the implementation of the People’s War on Terror in May of 2014, a police state has rapidly taken form in Xinjiang. By the beginning of 2017 the state had recruited “nearly 90,000 new police officers” and increased the public security budget of Xinjiang by 356 percent.[38] These new additions to the special-teams armed police force (wujing budui) are organized in a segmented manner throughout every prefecture and county in support of local Uyghur officers who staff checkpoints and work as informants at every level of Uyghur society. Because of widespread underemployment Uyghur officers have been drawn into the force in large numbers. Because of the stigma of their collaborator position and the tight supervision of their Han superiors, these Uyghur officers often treat Uyghur suspects even more harshly than Han officers. In general, the rising budget for the occupation police force has produced tremendous increases in surveillance technology and gridded policing infrastructure made through interlocking systems of walls, gates and “convenient” police checkpoints in cities and towns. Across the province, the state also began instituting regular inspections of the homes of Uyghurs.

During these inspections of homes in Uyghur neighborhoods, the police would first scan the QR code that they had installed on the front door of apartments.[39] Images and files associated with the registered occupants of the apartment would then be displayed on the police officer’s smart phone. Following this review of legal occupants, the police then would typically proceed to search the home for unregistered occupants. They look in closets, and under beds. They would vary the timing of inspection to make sure that the occupants would be unprepared. At times, they would ask to look through the books and magazines of the occupants. Other times they ask to inspect everyone’s phones and computers. Any refusal to comply meant that the person would be detained. If the occupants were not found to be home at the time of the inspection, they would be notified that they were required to appear at the police station within the next 24 hours.

At this time, in 2017, in the countryside such inspections were even more terrifying. There, the armed police were accompanied by groups of Han and conscripted Uyghur volunteers armed with clubs. They visited people’s homes on a regular basis to check their phones and computers for any unapproved religious material and to make sure that they were watching Chinese language television. They made sure that the men were not growing beards and the women were not covering their heads. They questioned Uyghur children in order to make sure that they were being sent to school and that their parents were not teaching them about Islam at home. They asked about mosque attendance, prayer times and whether or not they had ever listened to unapproved Islamic “teachings” (Uy: tabligh). They asked Uyghurs to attend weekly patriotic education meetings, sing patriotic songs, dance patriotic dances and pledge their undying loyalty to the Chinese state. Every household was responsible to send at least one member of the family to such meetings. Failure to comply with any of these forms of inspection and action resulted in arrest.

Since the People’s War on Terror was launched thousands of Uyghurs have been placed in indefinite detention.[40] As detainees they are forced to attend political education and Chinese-language education classes in reeducation centers. Thousands more have been serving sentences in labor camps for minor offenses (such as not attending political education meetings, praying or studying Islam illegally, wearing illegal clothes) under the new anti-terrorism and extremism laws. The detentions began in the summer of 2014 with young people (under the age of 55) who had practiced forms of reformist Islam being taken by the police and held without charge. The disappearance of youth into the depths of the police state was soon being euphemistically referred to as being taken behind “the black gate” (Uy: qara dereveze). Many of these initial detainees are still in detention at the time of writing, 3 years later.

Since February of 2017 there has been a new wave of detentions. Now it appears that any Muslim minority citizen, whether they be Hui, Kazakh or Uyghur, who does not advocate for the repression of religion and the assimilation of the Uyghur population can be seen as a threat to the state. As a Uyghur intellectual at one of the institutions in Ürümchi told me recently, “if you wear white shoes, they will arrest you for not wearing black shoes. If you wear black shoes, they will arrest you for not wearing white shoes.” He worried that he himself would be arrested after hearing that the president of Xinjiang University along with around 20 other Uyghur faculty members had been arrested for not teaching their courses on Uyghur literature solely in Chinese. Nearly all Uyghurs have a friend, colleague or family member who has been detained. Even Uyghur Communist Party members are not immune from detention. By the end of 2017 an estimated 1 million men and women had been sent to the “transformation through educations” centers that had been built across the region.[41]

In the spring of 2017 the local police were ordered to begin to rank Uyghurs using a number of metrics of extremist existence or behavior.[42] The primary categories of assessment were as follows:

1. Between Ages of 15 and 55

2. Ethnic Uyghur

3. Unemployed or underemployed

4. Possesses passport

5. Prays five times per day

6. Possesses religious knowledge or has participated in illegal religious activities (often meaning that the individual has studied Arabic or Turkish and/or listened to unapproved Islamic teachings)[43]

7. Has visited one of 26 banned countries (including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia among others).

8. Has overstayed a visa while traveling abroad.

9. Has an immediate relative living in a foreign country

10. Has taught children about Islam in their home

Any individual whose existence or behavior corresponded to three or more of these categories could be subject to questioning. Since two of the categories were simply being born Uyghur and being between the ages of 15 and 55, for many Uyghurs their very existence made them suspicious. Any individual that met five or more of these criteria could be subject to detention and political reeducation for a minimum of 30 days. Many were detained indefinitely. They were told that their beliefs and way of life were a form of social “cancer” (Uy: raq) that needed to be excised. They were told to celebrate the process of having their lives reengineered because it meant that they would be freed from “prejudice” (Uy: kemsitish) after they had been taught to despise their religion and lack of assimilation into Han society. Some among the detained and released Uyghurs and their relatives who I have interviewed in most depth have exhibited signs of post-traumatic stress. They said that small issues they encounter now result in deep feelings of anxiety. Many now have problems with panic attacks and depression.

After they or their loved ones were released they were often asked to write “vows of loyalty” (Ch: fasheng liangjian; Uy: ipade bildürüsh) to the state.[44] These statements force Uyghurs to articulate views that are not their own. The statements ask them to re-narrate their personal biographies in a way that places them in complete opposition to reformist Islam and in undying loyalty to the state. They strongly resemble the personal statements that many were forced to publicly declare during struggle sessions in the Cultural Revolution, but in this case they are racialized (i.e. Uyghur specific) and directly assimilationist, or oriented toward Han state culture. The gaslighting effect of the repetition and widespread circulation of these vows (particularly by well-respected Uyghur public figures) is one of the most potent tools of the reeducation campaign. It is here that the “thought-work” of social re-engineering is really taking place.

Many Uyghurs, like Alim who I introduced at the beginning of this essay, spoke with me about these processes of inspection, detention and harassment as a process of “breaking their spirit” (Uy: rohi sunghan). They said that when their loved ones came back to them they were changed as individuals. They were silent. They submitted to whatever they were asked to do. They were fearful. Something essential to their being was gone. The trauma of knowing that their life was in the hands of the police state made many of them lose hope. When they came back they began to parrot things they had been told in their classes. It was as if they had been reprogrammed. They said that the part of them that was Uyghur was broken, all that was left was a patriotic Chinese shell.

A four year old Uyghur child kisses an image of her father six months after he was taken to a reeducation camp for praying at a local mosque in rural Southern Xinjiang. Image by Eleanor Moseman

Conclusions

Chinese Framings of Terror Capitalism

The new framing of minority protests against state domination, Islamic piety movements and violent resistance as each a manifestation of “terrorism” has produced an academic growth industry across China. Centers for Terrorism Studies have sprung up across the country where Chinese academics reemphasize and validate the pronouncements of the state. The activities of several thousand Uyghurs in Turkey and Syria have been used as justification for the detention and re-education of hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs. The state of emergency and state funding that accompanied the People’s War on Terror has allowed for numerous experiments in securitization. As in the United States, new infrastructures of border security, biosecurity and cybersecurity are being introduced to buttress older forms of control. In the United States, counter-terrorism securitization is built on the legacy of the Cold War.[45] In China, counter-terrorism targets a specific group of native Muslim citizens and their resources. As such, the implementation of the “People’s War on Terror” is manifested differently in China than the “war on terror” elsewhere. It centers around a settler campaign that is facilitating the ongoing accumulation of natural resources from Uyghur lands. Accompanying this is a pervasive system of domination extending to all facets of Uyghur life.[46] In North America this type of thought work has not been forcibly implemented on a subjugated population in recent memory, though it is reminiscent of North American boarding schools where native populations that survived genocidal encounters with American pioneers were taught to embrace Christian values and denounce their “savagery.” In Afghanistan and Iraq, the United States military has attempted to “win the hearts and minds” of those whose land they have occupied, but that process was never as fully institutionalized as it is in contemporary Xinjiang. The US criminal justice system likewise attempts to rehabilitate inmates and turn them toward disciplined behavior while at the same time profiting from their incarceration. But in China, the “People’s War on Terror” is something different. In effect it is the outlawing of an entire way of life.

This process has been aided by the permissiveness of the world community toward the violent policing of Muslim populations. In particular, the Chinese case has found common ground with the Trump Administration’s policies towards Muslims. Many Chinese politicians and “terrorism studies” academics have applauded the Trump administration’s ban on Muslim travel.[47] They see it as validation for the travel restrictions the Chinese administration has imposed on Uyghurs. Meanwhile, the Chinese state has hired Erik Prince, the founder of the private mercenary army Blackwater, to set up training facilities for Chinese security forces in “counter-terrorism” activities targeting Tibetan and Uyghur populations. These direct linkages between American and European counter-terrorism efforts and the Chinese attempts to turn them on their own citizens, make framing Uyghur and Tibetan issues as merely domestic ethnic disputes increasingly untenable. This also makes it clear that domination and new sequences in racialization can be deployed in non-Western spaces. Like native groups elsewhere, the Uyghurs were asked to participate in a multiculturalist project whose contents were dictated by the state. They were asked to reengineer themselves along certain lines of permitted difference and accept the terms that were laid out to them. When they failed to do this, they found that the institutions of the state were used to sequester their bodies and destroy their families.

Today Uyghurs speak often of the brokenness they feel as a people. They say they have no words for how they feel. They say they can’t reconcile what is happening and who they are as human beings. When they say they are broken, they are saying that they are no longer whole as individuals. Their sense of self has been damaged. Mostly what they are saying is that they are terrified of how this will affect those they love. Stories of the systemic rape of women who have been detained circulate widely. Rumors of organs being harvested from young men accused of terror crimes are a part of daily conversation. Uyghurs worry that these stories are true or may become true. They worry that the biometric data that has been taken from them is part of some sort of systemic elimination process. They feel that they have nothing to protect themselves and those they love. They are being terrified by the normalization of terror capitalism and the way it is taking even limited forms of autonomy away from them.

Notes

[1] The “People’s War on Terror” names the ongoing state of emergency that was declared by the Chinese state in May 2014 following a series of violent incidents involving Uyghur and Han civilians. See Zhang Dan, “Xinjiang’s Party chief wages ‘people’s war’ against terrorism,” CNTV, May 26, 2014. <http://english.cntv.cn/2014/05/26/ARTI1401090207808564.shtml>

[2] Eric T Schluessel,”The Muslim Emperor of China: Everyday Politics in Colonial Xinjiang, 1877-1933.” PhD dissertation, Harvard University, 2016.

[3] Throughout this article Uyghurs are referred to as “natives.” This is the closest English approximation to the term yerliq which Uyghurs commonly use to refer to themselves. The term could also be translated as ‘local,’ but since yerliq also carries with it a feeling of indigeneity or rootedness to the land of Southern Xinjiang I have chosen to use “native” as a descriptor. Occasionally I also use the term “indigenous” (tuzhu) to refer to the knowledge and cultural practices that Uyghurs employ, but since this term is not in wide usage among Uyghurs (there is no translation for this term in Uyghur and in this context, its usage in Chinese is forbidden by the Chinese state), I do not use the term to describe Uyghurs themselves.

[4] The Hanafi school of Sunni Islam represents one of the largest populations within the Muslim world. Most Muslims in Turkey, Egypt, Central and South Asia subscribe to this juridical school. Nearly one-third of all Muslims across the world identify as Hanafi. It is typically described as one of the most flexible forms of pious orthopraxy with regard to relations with non-Muslims, individual freedom, gender relations, and economic activity. See Christie S. Warren, “The Hanafi School,” Oxford Bibliographies. <http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195390155/obo-9780195390155-0082.xml>

[5] Chris Horton, “The American mercenary behind Blackwater is helping China establish the new Silk Road.” Quartz, 2017. <https://qz.com/957704/the-american-mercenary-behind-blackwater-is-helping-china-establish-the-new-silk-road/>; and Rune Steenberg Reyhe, “Erik Prince Weighing Senate Bid While Tackling Xinjiang Security Challenge.” EurasiaNet Analysis, 2017. <http://www.eurasianet.org/node/85571>

[6] Human Rights Watch, “China: Free Xinjiang ‘Political Education’ Detainees,” 2017. <https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/09/10/china-free-xinjiang-political-education-detainees>

[7] Darren Byler and Eleanor Moseman, “Love and Fear among Rural Uyghur Youth during the ‘People’s War.’” Youth Circulations, 2017. <http://www.youthcirculations.com/blog/2017/11/14/love-and-fear-among-rural-uyghur-youth-during-the-peoples-war>

[8] Ann Laura Stoler and Carole McGranahan, “Refiguring Imperial Terrain” in Imperial Formations, eds. Ann Laura Stoler, Carole McGranahan, Peter Perdue. Santa Fe: School of Advanced Research, 2007. pp 3-42.

[9] ibid. 25.

[10] David Brophy, “The 1957-58 Xinjiang Committee Plenum and the Attack on ‘Local Nationalism.’” Wilson Center, December 11, 2017. <https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/the-1957-58-xinjiang-committee-plenum-and-the-attack-local-nationalism>

[11] Louisa Schein, Minority rules: The Miao and the feminine in China’s cultural politics, Duke University Press, 2000.

[12] Thomas Mullaney, Coming to terms with the nation: ethnic classification in modern China, Vol. 18, University of California Press, 2011.

[13] Brophy 2017

[14] Han Ziyong, ‘Han Ziyong: Xinjiang wenhua shi Zhongguo wenhua de yi ge buke huo que de siyuan.’ (Han Ziyong: Xinjiang culture is an indispensable resource for Chinese culture). CCTV.com, 12 June 2009. <http://news.cctv.com/xianchang/20090612/103290_1.shtml>

[15] Xinjiang Weiwuer Zizhiqu Bianjizu, Nanjiang Nongcun Shehui (Southern Xinjiang Village Society), Xinjiang Renmin Chuban She, 1953.

[16] Thum, Rian Thum, The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History, Harvard University Press, 2014.

[17] N. Becquelin, “Xinjiang in the Nineties.” The China Journal, Volume 44, 2000. pp. 65-90: 66.

[18] ibid. 67.

[19] See Shao Wei, “China Becomes Tomato Industry Target,” China Daily, June 15, 2012. <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2012-06/15/content_15506137.htm>

[20] N. Becquelin, “Staged Development in Xinjiang.” The China Quarterly, Volume 178, 2004. pp. 358-378.

[21] ibid. 365.

[22] ibid. 363.

[23] Emily T. Yeh, Taming Tibet: landscape transformation and the gift of Chinese development, Cornell University Press, 2013.

[24] Tom Cliff, “Lucrative Chaos: Interethnic Conflict as a Function of the Economic ‘Normalization’ of Southern Xinjiang,” in Hillman, B., & Tuttle, G. (Eds.), Ethnic Conflict and Protest in Tibet and Xinjiang: Unrest in China’s West, Columbia University Press, 2016. pp. 122-150.

[25] Based on interviews conducted by the author in 2014 and 2015.

[26] The Economist, “Let them shoot hoops,” The Economist, July 30, 2011. <http://www.economist.com/node/21524940>

[27] A simplified definition of this process of capitalist development and racialization is when state institutions that support the economic development of a dominant group allow the bodies and values of a dominant group to be read as superior to those of minority others. This basic form of racialization allows for the rapid dispossession of minority others through the institutions of the law, police, and the educational system. Because the bodies of minorities are read as inferior they are not granted the same protections as those seen as racially superior. This process of “original accumulation” and racialization is part of the logic capitalist development. See Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, University of North Carolina Press, 1983.

[28] Sareeta Amrute, Encoding Race, Encoding Class: Indian IT Workers in Berlin, Duke University Press, 2016. p. 14

[29] Uradyn E. Bulag, “Good Han, Bad Han: The Moral Parameters of Ethnopolitics in China,” in Mullaney, Thomas S., James Leibold, Stéphane Gros, and Eric Vanden Bussche, Critical Han Studies: The History, Representation, and Identity of China’s Majority, University of California Press, 2012. pp. 92-109

[30] ibid. 109.

[31] This is best exemplified by the lifetime imprisonment of the moderate Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti.

[32] “Ürümchi plans to complete 36 shantytowns reconstruction projects this year,” Central People’s Government, 2012. <http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2012-02/17/content_2069917.htm>

[33] G. Bovingdon, The Uyghurs: strangers in their own land, Columbia University Press, 2010.

[34] ibid. 120.

[35] Emily T. Yeh, “On ‘Terrorism’ and the Politics of Naming.” Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology, April 8, 2012. <https://culanth.org/fieldsights/102-on-terrorism-and-the-politics-of-naming>

[36] “The Race Card.” The Economist, September 3, 2016. <https://www.economist.com/news/china/21706327-leader-troubled-western-province-has-been-replaced-he-will-not-be-missed-its-ethnic>

[37] Based on interviews with state officials and failed applicants.

[38] Adrian Zenz and James Leibold, “Xinjiang’s Rapidly Evolving Security State.” China Brief, Volume 17, Issue 4, March 14, 2017. <https://jamestown.org/program/xinjiangs-rapidly-evolving-security-state/>

[39] These inspections were observed by the author during a year spent in Ürümchi in 2014 and 2015.

[40] Based on dozens of interviews conducted by the author with friends and relatives of those that had been arrested as well as interviews with government officials.

[41] Zenz, Adrian. (2018). “‘Thoroughly reforming them towards a healthy heart attitude’: China’s political re-education campaign in Xinjiang.” Central Asian Survey, 1-27.

[42] Based on interviews conducted by the author with Uyghurs who have been detained and released, the relatives of detainees as well as leaked official documents.

[43] Based on interviews conducted by the Uyghur intellectual Eset Sulayman and police officers in Kashgar prefecture, one of the main ways in which this religious knowledge is detected is when a Uyghur destroys his or her SIM card or refuses his or her phone to communicate with others. The lack of phone activity is read as a sign of deviance and results in an automatic interrogation. See Eset Sulayman “China Runs Region-wide Re-education Camps in Xinjiang for Uyghurs And Other Muslims,” September 11, 2017, Radio Free Asia. <http://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/training-camps-09112017154343.html>

[44] Here is an example from this widely circulated Communist Youth Party journal: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Fy2tcdVgOf8SVhPdNG0PhQ

[45] Joseph Masco. (2014). The theater of operations: National security affect from the Cold War to the War on Terror. Duke University Press.

[46] Darren Byler. (2017). “Imagining Re-Engineered Uyghurs in Northwest China.” Milestones: Commentary on the Islamic World.

[47] Al Jazeera. (2017. “China’s Communist Party hardens rhetoric on Islam.” <http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/03/china-communist-party-hardens-rhetoric-islam-170312171857797.html>; and Steenberg Reyhe, Rune. (2017). “Erik Prince Weighing Senate Bid While Tackling Xinjiang Security Challenge.” EurasiaNet Analysis. <http://www.eurasianet.org/node/85571>.

Chuǎng, issue #2 (2019)